Documenting Subsistence in Alaska: A Few Things Learned…

Jim Magdanz

Alaska Department of Fish and Game, Subsistence Division (retired)

UAF – Resilience and Adaptation Program, Graduate School, University of Alaska Fairbanks (Ph.D. student)

UW – Biocultural Anthropology (visiting student)

Friday March 14

3:30-5pm

Denny Hall 205

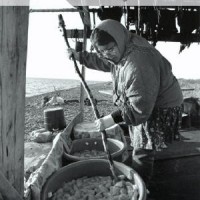

Jim Magdanz will present some results from 30-years of subsistence research in Alaska. Since 1980, state and federal laws have provided a priority for subsistence hunting and fishing over other consumptive uses such as commercial fishing. The state’s Division of Subsistence, directed primarily by anthropologists, became the primary source of information about Alaska’s subsistence economies. Jim was one of the Division’s earliest field researchers. He spent his 30-year career living and working in Nome, Kotzebue, and surrounding smaller communities. He will discuss the legal framework for Alaska’s subsistence priority, community population and harvest trends, their implications for sustainability, and social network analysis as a method to untangle the complex cooperative production systems in Native communities. Jim resigned from the Division of Subsistence in 2012 to pursue a Ph.D. in natural resources, and is currently a visiting graduate student in biocultural anthropology at UW.

About the speaker:

Jim is a Ph.D. student in natural resources and sustainability at the University of Alaska Fairbanks, and a visiting graduate student in biocultural anthropology at the University of Washington Seattle, with an emphasis on network analysis.

Jim came to Alaska as a photojournalist, fascinated by a group of 5-to-10-year-old Iñupiaq children he met during their visit to an Iowa dairy farm. Compared with children he knew, the Iñupiat were self-confident, calm, mature, and cooperative, not competitive. They shed no tears, threw no tantrums, and played with great joy. “What kind of place raises kids like this?” he wondered. So he went to Alaska, and spent the next 30 years of his life living in and studying small Iñupiaq communities in Arctic Alaska.

In 1981, he joined the Division of Subsistence, a small social science research group embedded in the Alaska Department of Fish and Game. In his first project, a “simple” subsistence harvest estimation problem developed into a continuing interest in network analysis as a method to understand rural economies. Analyses showed that Iñupiat produced and distributed wild foods within multi-household, extended family structures very similar to those of their ancestors, despite profound social and economic changes over the last century. As his investments in network research grew, he realized he needed to improve his network analysis skills, so he resigned to return to graduate school full time.